| Original Article | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sudan J Paed. 2023; 23(1): 32-41 SUDANESE JOURNAL OF PAEDIATRICS 2023; Vol 23, Issue No. 1 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Treatment outcomes and associated factors among children with severe acute malnutrition at Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort studyAddis Aye (1), Frehiwot Amare (2), Teshome Sosengo (1)(1) School of Pharmacy, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia (2) School of Pharmacy, Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Correspondence to: Teshome Sosengo School of Pharmacy, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia. Email: teshomesosengo [at] gmail.com Received: 01 November 2021 | Accepted: 03 December 2021 How to cite this article: Aye A, Amare F, Sosengo T. Treatment outcomes and associated factors Among children with severe acute malnutrition at Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. Sudan J Paediatr. 2023;23(1):32–41. https://10.24911/SJP.106-1635757512 © 2023 SUDANESE JOURNAL OF PAEDIATRICS

ABSTRACTEthiopia is one of the countries with the highest under-five child mortality rates, with malnutrition remaining the major cause of death. Overall, 10% of children in Ethiopia are wasted, and 3% are severely wasted. To assess the treatment outcomes and associated factors among children with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) at Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia, data of 162 under-five children admitted from January to December, 2020, at Hiwot Fana Specialized University hospital were collected retrospectively from 1 January to 20 February 2021. Pre-tested structured questionnaire was used to extract data from medical records. The data was entered into Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 21 for analysis. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. In this study, 162 participants were included and 54% were males. The majority (80.2%) of children were newly admitted and 49.7% had less than 7 days of hospital stay, 70.99% recovered from malnutrition, and 42.6% had marasmus. Amoxicillin and gentamycin combination (47.5%) was the most commonly prescribed intravenous antibiotics. Having diarrhoea (AOR=22, 95% CI: 2.86–169.46), presence of comorbidities such as malaria (AOR=103.29, 95% CI: 7.42–1437.74) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (AOR=42.72, 95% CI: 4.47–408.23) were statistically associated with poor recovery from severe malnutrition. More than 70% of children with SAM had good treatment outcomes. Child vaccination history, length of hospital stay, admission weight for height, and presence of comorbidities such as diarrhoea, pneumonia, measles, HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis were factors associated with bad malnutrition and treatment outcomes. Keywords:Severe acute malnutrition; Under-five children; Mortality, Treatment outcome; Ethiopia. INTRODUCTIONMalnutrition is an abnormal physiological condition caused by deficiencies, excesses, or imbalances in energy, protein, and/or other nutrients. Malnutrition can be either undernutrition or overnutrition (obesity). There are four forms of undernutrition: acute malnutrition, stunting, under-weight, and micronutrient deficiencies. This can also be categorized as either moderate or severe malnutrition and can appear isolated or in combination, but most often overlap in one person or population [1]. Severe acute malnutrition (SAM) is a major public health problem in the whole world. SAM is defined as a weight-for-height measurement of 70% or less below the median or 3 SD or more below the mean international reference values, the presence of bilateral pitting oedema, or a mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) of less than 115 mm in children [2]. More than 820 million people in the world are still hungry today, underscoring the immense challenge of achieving a zero hunger target by 2030. Hunger is rising in almost all Sub-regions of Africa and, to a lesser extent, in Latin America and Western Asia. It is estimated that there are nearly 232.5 million who suffer from hunger worldwide in Africa [3]. Nearly 24 million children (younger than 5 years) experience SAM and 19 million severely wasted children are living in developing countries. It is common in sub-Saharan Africa, with approximately 3% of children under five affected at any one time. It is also associated with several 100,000 child deaths each year [4]. The poor nutritional status of children and women continues to be a serious problem in Ethiopia. Overall, 10% of children in Ethiopia are wasted, and 3% are severely wasted (below 3 SD). The health sector has increased its efforts to enhance good nutritional practices through health education, treatment of extremely malnourished children, and provision of micronutrients [5]. SAM remains remarkably large and at the same time, its prevalence has not been significantly reduced during the past three decades [6]. A hospital-based study in Ethiopia revealed that there is an alarming low cure and high death rate of 46% and 29%, respectively, from SAM [7]. Such high mortality in inpatient units has been attributed to either comorbidities such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and diarrhoea or to poor adherence to the existing therapeutic guidelines [8]. In Ethiopia, 82% of all cases of child malnutrition and its related pathologies are not appropriately treated or left untreated [9]. There are two treatment modalities of SAM in which patients with failed appetite and/or with a major medical complication are initially admitted to an in-patient facility to treat the complications and stabilize their clinical situation. Whenever patients have a good appetite and no major medical complications or do not have oedema and marasmus kwashiorkor, they enter to the out-patient treatment program directly. The children that were initially admitted to in-patients are also transferred to the outpatient once the complications are addressed and appetite is regained [10]. In Ethiopia, the health sector has attempted to upgrade nutritional interventions and improve treatment outcomes through health promotion, effective treatment strategies, and supplementation of essential micronutrients for children and mothers. Different small-scale fragmented studies have been conducted to determine the treatment outcomes of children with SAM. However, the evidence based on previous studies on the treatment outcomes and factors associated with SAM is inconsistent and remains inconclusive. This suggests that the prevention and management of SAM is not uniform and the presence of unfinished agendas across the country may be because of lack of access to relevant healthcare or inconsistence (R) use of SAM treatment protocols [11,12]. ObjectivesGeneral objective

Specific objectives

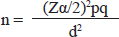

MATERIALS AND METHODSStudy area and periodThe study was conducted at Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia. Harar is found in the eastern part of Ethiopia and it is located 526 km away from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. The data was collected retrospectively from 1 January to 20 February 2021 from a medical record of under-five children admitted to HFSUH from January to December 2020. Study designAn institution-based retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted. Study populationMedical records of children with SAM with age above 6 months. Sample size determinationThe sample size was determined by using a single population proportion formula by taking a prevalence (P) of recovery (77.8%) among children with severe malnutrition from a study conducted in Jimma, Ethiopia [13] and calculated at 95% confidence level and ±5% margin of error. Finally, a 10% nonresponse rate was added.

where: n=required sample size Zα/2=standard score (1.96) corresponding to 95% confidence level d=margin of error (0.05) q=1-p

Since the total population is less than 10,000. The sample size reduction correction formula was used. The number of children with severe malnutrition from 1 January to 31 December 2020 at Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital was 320. Nf=n/ (1 + n/N) Nf=265/ (1 + 265/320)=145 where; Nf=corrected sample size n=total number of sample size N=number of children with severe malnutrition By adding 10% for compensation of missing (incomplete) data, the final sample size was 160. Sampling techniqueTo select the study subject, a systematic sampling method was used K=N/n K=2,272/242=9 The first study participant was selected using a lottery and then at every nine patients. The patients’ medical registration was used as a sampling frame. When eligible patient medical charts were found that were not fulfilling criteria, the next patient medical chart was considered. Data collection techniqueData was collected by using data abstraction format by reviewing the patient’s medical charts. Data processing and analysisThe collected data was checked for accuracy, consistency, irregularities, omission and then precoded data entered into Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 21 for analysis. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify the association of independent variables with the dependent variables. The variable with a p-value ≤ 0.25 in the bivariate analysis was further analysed in a multivariate logistic regression model. The finding was presented using the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The finding was presented using tables and graphs. Operational definitionsDeath: a child dying during its stay in the outpatient therapeutic feeding program and those who have died in transit from the outpatient therapeutic feeding program site to inpatient care but have failed to reach the inpatient therapeutic feeding program. Kwashiorkor: there is severe undernutrition or malnutrition in children resulting from a diet excessively high in carbohydrates and low protein. Marasmus Kwashiorkor: Weigh-for-height (W/H) <70% with oedema or MUAC <11 cm with oedema. New admission: patients that are directly admitted to a therapeutic feeding centre to start a nutritional treatment. Readmission: patients that are declared cured or recovered but relapsed to be admitted to the outpatient therapeutic feeding program. Recovered: are those individuals who have become free from medical complications and have achieved and maintained sufficient weight gain (Sphere.) Sever wasting or marasmus: W/H less than −3 SD (z score) or less than 70% of the median GROWTH standard, or MUAC less than 115 mm in children aged 6–59 months. SAM: it is defined by an extremely low weight-for-height, by visible severe wasting (marasmus), and/or by the presence of nutritional oedema (kwashiorkor). Stunting: individuals whose height is below the average expected height for their age. Successful treatment outcome: this is an outcome of children under outpatient therapeutic feeding program treatment who discharged recovered. RESULTSSocio-demographic characteristics of childrenData were extracted from a medical record of 162 children with SAM. A total of 80 data were excluded from the study due to missing either two or more socio-demographic characteristics or associated risk factors. Among the eligible children, more than half (53.7%) of them were within 6–59 months of the age group with a mean age of 21.78 ± 10.387 (mean ± SD) months and 87 (54%) of the study participants were male. The majority (80.2%) of the eligible children were newly admitted and nearly half (49.7%) of the study participants had less than 7 days hospital stay. Sixty-nine (42.6%) of the children were admitted due to marasmus and about two-thirds (67.3%) of the study participants were fully immunized for their age while a 126 (77.8%) of them had exclusive breastfeeding. Among the eligible children, only 19 (11.7%) of them were orphans, while 85 (52.5%) of them had adequate sunlight exposure during their early life (Table 1). Medical comorbidity at admissionAmong the study participants, 67.9% of them had fever while 94 (58%) had oedema. The most common comorbidities in this study (Table 2) were hypoglycaemia (43.8%), pneumonia (42%), gastroenteritis (39.5%), diarrhoea (38.3%), cough (29%) and anaemia (25.9%). Provision of treatmentThe management of under-five children that were admitted with SAM to the paediatrics ward showed that IV antibiotics were prescribed to 101 (68.52%) of them, amoxicillin and gentamycin combination was the most commonly prescribed IV antibiotics (47.5%) in this study (Table 3). The other most prescribed medications were vitamin A (43.8%), folic acid (43.2%), and albendazole or mebendazole (37%). Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of children with SAM (n=162).

Table 2. Medical comorbidities among children with severe acute malnutrition (n=162).

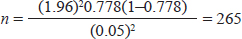

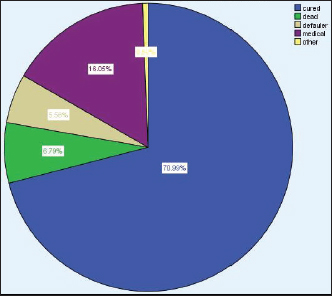

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus. Treatment Outcomes of under-five children with SAMOut of 162 admitted children with SAM, 111 (70.99%) cases recovered from SAM, whereas 11(6.8%) cases died because of SAM (Figure 1). Treatment outcome of SAM by type of diagnosis in the treatment centresThe predominant form of malnutrition in this study was marasmus 69 (42.6%), followed by kwashiorkor 55 (34%). Among the children who presented with marasmus, 48 of them were recovered while 4 died. While among the patients presented with kwashiorkor, 40 of them were recovered while 4 of them died. However, regarding the 3 stunted children, all of them recovered (Figure 2). Table 3. Distribution of treatment for children with SAM (n=162.

Figure 1. Treatment outcome of children with SAM (n=162). Determinants of treatment outcomesIn the bivariate logistic regression, child vaccination history, presence of nasogastric (NG) tubes, admission, weight for height, and presence of comorbidities such as diarrhoea, pneumonia, measles, HIV, malaria, sepsis were factors with a p-value of < 0.25 and hence selected for the multivariate model. In multivariate logistic regression, children with diarrhoea were 22 times more likely to have poor treatment outcomes (AOR=22, 95% CI: 2.86–169.46) compared to counterparts and children who were on NG tube during treatment and were 6.85 times more likely to have poor treatment adherence (AOR=6.85, 95%CI: 1.82–23.84). Furthermore, the presence of comorbidities such as malaria (AOR=103.29, 95% CI: 7.42–1437.74), HIV (AOR=42.72, 95% CI: 4.47–408.23) and sepsis (AOR=0.17, 95% CI: 0.19–1.49) were found to be associated with poor SAM treatment outcome. The other socio-demographic and clinical profiles were not significantly associated with the treatment outcome of children, both in bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 4).

Figure 2. Treatment outcome by type of malnutrition among children with SAM (n=162). Table 4. Predictors of treatment outcome among children with SAM (n=162).

*statistically significant. AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; COR, correlation coefficient. DISCUSSIONThe present study mainly aimed to report on the treatment outcomes of SAM and associated factors with it among fewer than children. The findings of this study showed that, of the study participants with SAM and with known outcome, 70.99% were cured. This is comparable to the recovery rate reported by a previous study in Southwest Ethiopia, which has reported 67.7% of the cure rate among children treated for SAM [14]. However, the finding is higher compared to studies conducted in Lusaka, Zambia (53.7%) [15], Tigray (61.7%) [16], Jimma (45%) [6], Tamale Teaching Hospital in Tamale, Ghana (33.6%) [14] and India (53.4%) [9]. On the other hand, the treatment response was poor compared to a similar study conducted in Southern Bangladesh (92%) [17], findings from Jimma University Specialized Hospital, Ethiopia (87%) [18], and Woldia General Hospital, Ethiopia (85%) [19]. This difference could be due to differences in socio-economic status, quality of care provided for children, health-seeking behaviour, availability as well as accessibility of therapeutic foods and medications. In the present study, the mortality rate due to SAM is 6.8%. This finding is higher than the mortality rate reported from Tigray, Ethiopia (3.02%) [20] and India (1.1%) [9]. However, it was relatively less than reports from Uganda (11.9%) [21] and Sudan (9.3%) [7]. The higher mortality in this study could be due to poor quality management of SAM and medical complications associated with SAM. In the current study, the overall defaulter rate is 5.6% which is by far lower than the report from Tigray, Ethiopia (17.5%) [15], and Wolaita zone, Ethiopia (2.2%) [22]. Besides, marasmus was found to be the predominant form of malnutrition in this study (42.6%), which was less than the study found from Tigray region, Ethiopia (98.4%) [15] and Wolaita zone, Ethiopia [22]. This may be explained by the fact that marasmus is more common in the age group below two years, which is the case in this study in which 67.3 % of the study population lies in the age category less than 2 years. The present study showed that of children who were admitted with SAM, 42% have pneumonia, 38.3% have diarrhoea, and 13% have tuberculosis. A study conducted in Yakatit 12 Hospital in Addis Ababa showed that of all severely malnourished children 24.3% have pneumonia, 11% have tuberculosis, and 21% have diarrhoea [23]. The most commonly prescribed medications in the current study were IV antibiotics (68.52%). This is in line with a previous study conducted in Tigray region, Ethiopia, which reported that antibiotics were the most commonly prescribed medication in children treated for SAM [15]. In contrary to this, a study conducted in Debremarkos referral hospital, Ethiopia, the most commonly prescribed medication in children admitted to SAM was vitamin A (82.6%) and folic acid (83.8%) [24]. In this study, children with diarrhoea were 22 times more likely to have poor treatment outcome [AOR=22, 95%CI: 2.86–169.46]. This is in agreement with a study finding from Chad which showed significant associations between not cured and diarrhoea [25]. HIV-positive children had 42.72 times higher probability of poor recovery from SAM compared to HIV-negative children (AOR=42.72, 95%CI: 4.47–408.23). This is in line with the study conducted in Woldia General Hospital, Ethiopia [19] and northern Ethiopia [25]. The effects of HIV/AIDS and malnutrition are interconnected and worsen one another in a vicious cycle. In line with the present study findings, the presence of tuberculosis comorbidity was reported as an independent predictor of mortality in a study conducted in Southwest Ethiopia [26]. Tuberculosis worsens undernutrition as patients with active tuberculosis are often in a catabolic state and experience weight loss from decreased dietary intake as a result of loss of appetite, nausea, and abdominal pain. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONSMore than 70% of children with SAM had good treatment outcomes. The majority of the admitted children have marasmus type of malnutrition. The presence of diarrhoea, NG-tube during treatment, or the presence of comorbidities such as malaria, HIV, and Tuberculosis were the factors found to predict the treatment outcome among children treated for SAM. Due attention should be given to the hospital management for improving the capacity of the hospital to provide proper management of SAM. Additionally, comorbid diseases have to be managed appropriately to increase recovery rates. ACKNOWLEDGMENTThe authors acknowledge Haramaya University College of Health and Medical Sciences for all positive cooperation in the undertaking of this study. CONFLICT OF INTERESTThe authors declare no conflict of interest FUNDINGNone. ETHICAL APPROVALEthical clearance was obtained from School of Pharmacy College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University. A formal letter from the College of Health and Medical Sciences was communicated to Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital and respective responsible bodies. The study is a retrospective (record-based) study. No names were used for data collection. Participants’ consent is not required according to the approved research guidelines, and confidentiality was ensured at all levels. REFERENCES

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Aye A, Amare F, Sosengo T. Treatment outcomes and associated factors among children with severe acute malnutrition at Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. Sudan J Paed. 2023; 23(1): 32-41. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1635757512 Web Style Aye A, Amare F, Sosengo T. Treatment outcomes and associated factors among children with severe acute malnutrition at Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. https://sudanjp.com//?mno=137163 [Access: May 08, 2024]. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1635757512 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Aye A, Amare F, Sosengo T. Treatment outcomes and associated factors among children with severe acute malnutrition at Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. Sudan J Paed. 2023; 23(1): 32-41. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1635757512 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Aye A, Amare F, Sosengo T. Treatment outcomes and associated factors among children with severe acute malnutrition at Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. Sudan J Paed. (2023), [cited May 08, 2024]; 23(1): 32-41. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1635757512 Harvard Style Aye, A., Amare, . F. & Sosengo, . T. (2023) Treatment outcomes and associated factors among children with severe acute malnutrition at Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. Sudan J Paed, 23 (1), 32-41. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1635757512 Turabian Style Aye, Addis, Frehiwot Amare, and Teshome Sosengo. 2023. Treatment outcomes and associated factors among children with severe acute malnutrition at Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics, 23 (1), 32-41. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1635757512 Chicago Style Aye, Addis, Frehiwot Amare, and Teshome Sosengo. "Treatment outcomes and associated factors among children with severe acute malnutrition at Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study." Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics 23 (2023), 32-41. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1635757512 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Aye, Addis, Frehiwot Amare, and Teshome Sosengo. "Treatment outcomes and associated factors among children with severe acute malnutrition at Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study." Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics 23.1 (2023), 32-41. Print. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1635757512 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Aye, A., Amare, . F. & Sosengo, . T. (2023) Treatment outcomes and associated factors among children with severe acute malnutrition at Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics, 23 (1), 32-41. doi:10.24911/SJP.106-1635757512 |

Nagwa Salih, Ishag Eisa, Daresalam Ishag, Intisar Ibrahim, Sulafa Ali

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 24-27

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.4

Siba Prosad Paul, Emily Natasha Kirkham, Katherine Amy Hawton, Paul Anthony Mannix

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(2): 5-14

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1519511375

Inaam Noureldyme Mohammed, Soad Abdalaziz Suliman, Maha A Elseed, Ahlam Abdalrhman Hamed, Mohamed Osman Babiker, Shaimaa Osman Taha

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 48-56

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.7

Adnan Mahmmood Usmani; Sultan Ayoub Meo

Sudan J Paed. 2011; 11(1): 6-7

» Abstract

Mustafa Abdalla M. Salih, Mohammed Osman Swar

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 2-5

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.1

Amir Babiker, Afnan Alawi, Mohsen Al Atawi, Ibrahim Al Alwan

Sudan J Paed. 2020; 20(1): 13-19

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1587138942

Hafsa Raheel, Shabana Tharkar

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 28-38

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.5

Anita Mehta, Arvind Kumar Rathi, Komal Prasad Kushwaha, Abhishek Singh

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 39-47

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.6

Majid Alfadhel, Amir Babiker

Sudan J Paed. 2018; 18(1): 10-23

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2018.1.3

Bashir Abdrhman Bashir, Suhair Abdrahim Othman

Sudan J Paed. 2019; 19(2): 81-83

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1566075225

Amir Babiker, Mohammed Al Dubayee

Sudan J Paed. 2017; 17(2): 11-20

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2017.2.12

Cited : 8 times [Click to see citing articles]

Mustafa Abdalla M Salih; Satti Abdelrahim Satti

Sudan J Paed. 2011; 11(2): 4-5

» Abstract

Cited : 4 times [Click to see citing articles]

Hasan Awadalla Hashim, Eltigani Mohamed Ahmed Ali

Sudan J Paed. 2017; 17(2): 35-41

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.2017.2.4

Cited : 4 times [Click to see citing articles]

Amir Babiker, Afnan Alawi, Mohsen Al Atawi, Ibrahim Al Alwan

Sudan J Paed. 2020; 20(1): 13-19

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1587138942

Cited : 4 times [Click to see citing articles]

Mutasim I. Khalil, Mustafa A. Salih, Ali A. Mustafa

Sudan J Paed. 2020; 20(1): 10-12

» Abstract » doi: 10.24911/SJP.1061585398078

Cited : 4 times [Click to see citing articles]